(Tania James, 2023)

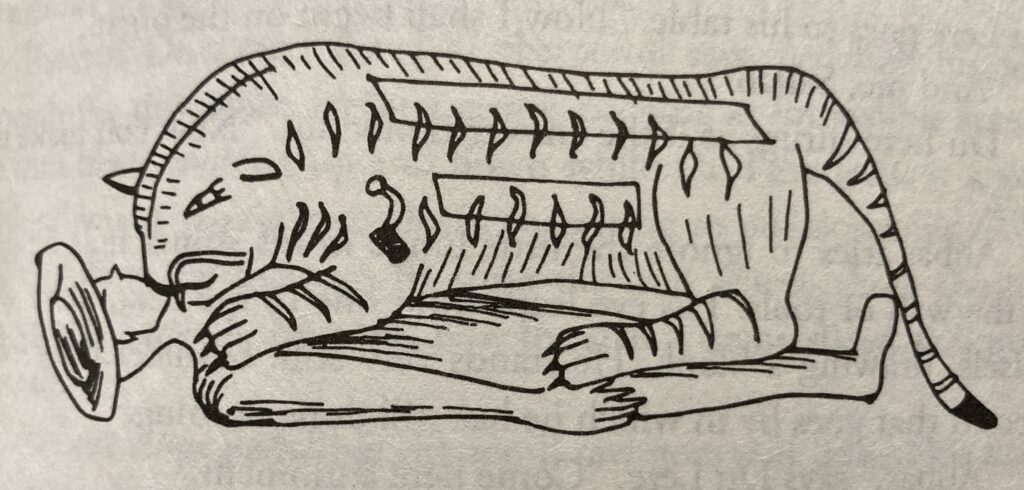

Hastily Du Leze draws atop the sketch, explaining how the tiger will be hollow, with a bellows in the head and a pipe organ in the body. A lateral slice just above the tiger’s ears will create a sort of lid, which, when removed, will expose the organ pipes. A door along its rib cage will open onto a set of ivory keys, to be operated by an organ player poised by the tiger’s left flank.

“…the kingdom of Mysore is developing new inventions and creations in all fields, from medicine to botany to metalsmithing. I have employed French and English artisans to show us how to copy all variety of their devices, from improved muskets to scissors to hourglasses to barometers that actually work.

“And now…I present another innovation, made by a Frenchman some of you may know. He is Musa Lucien Du Leze, the greatest clockmaker in France and a true friend of Mysore…suffice to say that this fantastical curiosity serves a purpose different from that of all the other innovations I have commissioned – yet equally important.” Tipu pauses meaningfully. “This one extends the imagination.”

…Du Leze moves to his position between the tiger and the wall. He opens the door along the flank to expose the organ keys, which the audience will not be able to see….

Whenever Du Leze has practiced playing in the workshop, Abbase has found the organ music to be nasal and discordant, a sort of whiny harmonium. Now he realizes the organ notes were trapped by the workshop’s low ceiling. In the Rag Mahal, they soar.

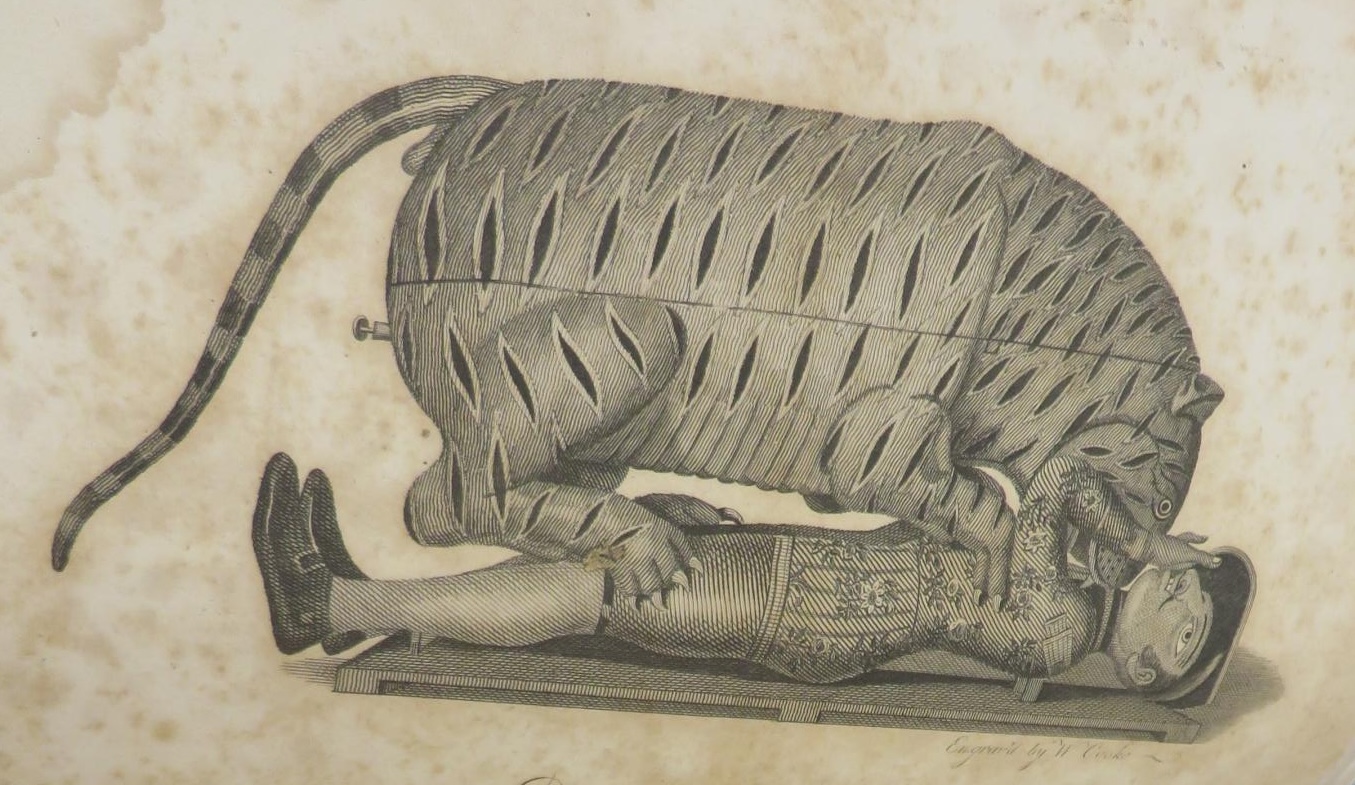

Tania James’s novel Loot offers a speculative fictional account of a real artefact: the tiger organ commissioned by Tipu Sultan sometime between 1782 and 1799, when he was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in South India. Throughout his rule Tipu Sultan fought against the British East India Company, whose army ultimately defeated him and looted his city of Seringapatam. The tiger was Tipu’s symbol, and his tiger organ portrayed the great cat mauling a British soldier. Pipes in the tiger’s and man’s heads simulate roaring and wailing, respectively, and are activated by a hand crank. Meanwhile inside the tiger’s body is an organ with two ranks of pipes, played from a row of circular keys. Upon Tipu’s defeat his organ was taken to London and put on display, where it remains to this day: known as “Tippoo’s Tiger,” it is a favorite object in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

James’s novel aptly characterizes Tipu’s tiger-organ as an innovation “that extends the imagination,” and her portrayal extends the lively imaginary life this artefact has led. Accounts of the organ preceded its arrival in London, and portrayed it as a fully automated instrument of infernal music consisting entirely of cries and moans – which is to say, its two rows of organ pipes had no place in this auditory imagination. After the instrument’s arrival, a widely repeated account maintained, “Upon the instrument, it is said, Tippoo would often exercise his skill, with no other view than to excite in his imagination those acute agonies in which it was his common practice to indulge.” Adopting Tipu’s tiger organ into our Museum, we find in the instrument an echo of the Bull of Phalaris, and the revenge of the cat piano.

Text: Tania James, Loot (New York: Vintage Books, 2023), p. 23, pp. 57-58.

Images: Tania James, Loot (New York: Vintage Books, 2023); James Salmond, A Review of the Origin, Progress, and Result of the Decisive War with the late Tippoo Sultaun, in Mysore (London 1800)